Join the Slovenian School Reading Group at Philosophy Portal.

Beginning September 24th, we will start with Alenka Zupančič’s The Odd One In.

To participate, become a paid member of my Substack or subscribe to my Patreon

Head over to Philosophyportal.online to learn more.

Since before the dawn of my intellectual activities I’ve always read texts out of context. And far from being a bug that prevents me from reaching the true core of a theoretical edifice, it is a feature that comes with going for real speculations. It’s self-evident that Hegel did not mean his Phenomenology of Spirit with its stages to be superimposed on the development of “a lineage of thought that runs from Richard Dawkins’ reason, through Sam Harris’s spirituality, and Jordan B. Peterson’s religiosity.”1 But this is exactly what

has done in his latest book:“This popular intellectual lineage outlines the way the zeitgeist of our culture in the 21st century is literally attempting to re-process the phenomenological struggle embedded in Hegel’s Phenomenology (specifically: reason, spirit, religion). The conclusion offers what I think is the most important theopolitical framework for exiting that culture war, and entering into a new 21st century struggle for a socialist politics: Christian Atheism.”2

To recapitulate:

Reason → Richard Dawkins’ anti-fundamentalist New Atheism

Spirit → Sam Harris’ scientifically informed Eastern-like Spirituality

Religion → Jordan B. Peterson’s psychological-aesthetic Cultural Christianity

As Cadell Last convincingly shows, each of these figures embodies a certain spiritual form that constitutes itself in the gap of the other. Questions of spirituality emerge from the gap of lifeless or soulless reason, and questions of religion emerge from the gap of the solitary and affective nature of spirituality.

Besides their differences, he draws our attention to what unites all these figures, namely their opposition to woke. As a result, these three figures are blind to “the most important theopolitical framework,” which situates itself in an immanent critique of the left.

Last speaks about the fact that Dawkins has not changed much since his rise to fame (originating in 9/11). Ever since, Dawkins has understood himself as a cultural Christian, meaning that he does not attribute any deeper metaphysical meaning to the Christian tradition, but that he still appreciates the aesthetic beauty of its works such as cathedrals and hymns. Even though Jordan B. Peterson may appear to be a devout religious man staunchly against Dawkins’ atheism, he actually identifies with that very same term. Peterson merely argues that not the belief in God, but to act as if God exists is necessary for maintaining a value-hierarchy without which society self-destructs in undifferentiated chaos. Last writes:

“[These are the] two different variants of “Cultural Christianity”: the Dawkins form and the Peterson form:

1. the Dawkins form of “Cultural Christianity” attempts to emphasise the importance of modern liberal social morality without the need for an absolute or a supernatural dimension; and

2. the Peterson form of “Cultural Christianity” emphasises a social morality with support from traditional myths of the absolute or a supernatural dimension (their “psychological significance”).”3

Unlike Dawkins’ crude affirmation of secular reason, Peterson acknowledges the horrific results of secular post-enlightenment forms of social morality. Based on that, Peterson recoils from anything associated with it, including the immanent self-critique of post-enlightenment movements that have emerged alongside them, the foremost name of which is Marxism. Instead of a head-on thinking with the mess of our theopolitical-economic situation — exemplified by the current wars which

is constantly writing about — Peterson asserts a traditionalist form of Christian nationalism. While framing himself as a protector of family values, he ignores the very basis of what constitutes it: relative socioeconomic dignity conducive to child-rearing, which is increasingly waning. Far from being a bulwark against the profanity of market dynamics, Petersonian traditionalism serves the incessant self-revolutionising of capitalism in the name of its opposite, traditional religion ensuring stability.Here, we shouldn’t fail to mention that Russia, profiling itself as a Christian conservative country defending itself against woke satanism, as well as the Israeli state, whose leaders are legitimising their Greater Israel project with scriptures from the old testament, are totally aligned with a type of Petersonian justification of the status quo in service to the invasion of Ukraine, and the genocide of the Palestinians respectively. Putin’s regime as well as the IDF both frame themselves as supported by God in a holy war against evil.

If these three figures, despite their differences, are against woke and communism, then, from the Marxist viewpoint we can see that the unity of these figures and woke are on the side of capital, our one true God. And, crucially, from the Christian Atheist viewpoint, we know that we cannot help but serve this God. The religious saying that our belief in God is irrelevant insofar as we have no choice but to serve, love and be subjected to him has its truth here:

“Capital can effectively appear as a new embodiment of the Hegelian Spirit, an abstract monster which moves and mediates itself, parasitising the activity of actual, really existing individuals.”4 (Slavoj Žižek, Less Than Nothing)

Following Hegel, Christianity is special according to Žižek and Last because atheism inheres in its core, as its truth. The cross symbolises God not being one with himself. Marxism then, points to the cross of capital. Not only at the hand of capital itself, but by the self-abolition of the proletariat. Chris Cutrone writes:

“The politically strategic vision of Marxism was that, to break the repetitive cycle of capitalist crisis and destruction, the wage-laborers would need to abolish wage labor — the laborers would need to abolish labor. It was not enough that the capitalists destroyed capitalism — that capitalism destroyed capital. The very basis for the reproduction of capital — labor — must be overcome.”5

Last’s Real Speculations is to be understood within his larger project to think our historical moment as a political act, holding the immanent contemporary antagonisms visible in the dialectical historicity of New Atheism, as well as pointing beyond them by uncovering what is necessarily repressed and disavowed in their edifices. Last again:

“If there is a fundamental service that “real speculations” is trying to guide, stated very simply it is this: the sublation of the Petersonian moment of religion which leaves us in a psychological wrestling with traditional myths (and fails to engage modern philosophy on its own terms and towards its own aims); and the speculative affirmation of the Zizekian moment of absolute knowing, which forces us to re-think a socialist spirit for a renewed theopolitical-economy.”6

During the talk Cadell Last and I had at the recent Wake festival (May 1st 2025) someone in the audience stood up and accused us of not being humble. Prima facie, Last’s style and mine might seem to make scathing generalisations, to lack complexity and nuance. Rather, this is how the materialist dialectic necessarily appears in its immediacy. But it’s not that Cadell’s real speculations aren’t non-complex or simply linear in a progressive, teleological sense. In passing, I want to mention the chapter on The Field of Nietzschean Interpretation, which is a fantastic analysis of thinkers orbiting Nietzsche’s thought. This text is a great philosophical feat, clarifying how Nietzsche is situated in the history of philosophy.

But apart from that, the lesson of speculative thought is that all multi-faceted mediations, circle of circles, or triad of triads, lapse back into the abstract immediacy of the I. One thing that I have always found special about Last’s philosophical performativity is the lack of fixity to adherence of the theoretical edifices of modern philosophy (in the sense of strict obedience to abstractly universal terminology) along with a keen eye to the personalisation of these dense theories without losing out on rigorous fidelity. It’s that simple and determined style of his that appears as a closure to the type of thought that guards itself against the truth that differentiation has its origin in singularity.

Back to the topic of reading out of context. Can we really equate all these pop intellectuals and the development of the zeitgeist of the last decades with the last three stages of Hegel’s Phenomenology? Should we?

How to handle such a question? Let’s start by transposing the form of this question to a different content and then apply it to Hegel himself. How does Hegel ground these stages in his Phenomenology, or, better yet, how does Hegel ground his mature system as such? For Hegelians, Hegel’s system of thought, what he calls his encyclopedic system of philosophical sciences, is what it is. God has three modes (logic, nature and spirit). Each of these modes are further differentiated into their triads, of which each element consists of a triad and so on and so on. For example, God’s mode of logic consists of the triad being, essence and concept. The third moment of God’s mode spirit is absolute spirit which is made up of art, religion and philosophy. Objective Spirit has ethical life for its third moment, which is made up of the family, society and the state. One of the reasons Hegel’s philosophy helps one to think creatively is because one is compelled to think the dialectical interrelations of these triads, to speculate with them. For example, by superimposing the logical structure on the spiritual structure, which shows that art is on the level of the logic of being, or that nature is the opposite of God within himself, just like Christ is the opposite of the Father, without whom there would be no Holy Spirit, which is what God is beyond one-sided transcendence or one-sided immanence.

Yet, this is all besides the point. My point is that this whole system consists of Hegel’s contingent decisions. In a sense, Hegel never really finished the Science of Logic (and hence his system). Up until the end of his career, he kept coming back to it, changing the order of categorisation, adding remarks and so on, repetitiously grounding new decisions. So what is at stake here? Whereas Hegel’s system seems to be a closed totality made up of necessary moments that are starkly in their proper place, this totality seems to fall apart if we take into account the process of Hegel as an active thinker who kept editing his work. It is only after the fact (and especially after his death) that we see his thought-system as the necessary, final and definitive foundation from which thought can speculate (if we decide to take him up). But, as a matter of fact, it is very strange for Hegel to say that his speculative philosophy is a combination of mysticism and science. It is also very strange that Hegel would say that he is a Lutheran, when his system of God has these triadic modes of which the second moment of nature can be equated with Spinoza’s God. One can argue that Hegel’s eclecticism is preposterous, evidently self-contradictory and contingent. An orthodox Hegelian could come along and explain that it is all necessary after all, that each moment has to be contextualized within his system. And he would not be wrong. Yet, besides that, to paraphrase Daniel Garner of

regarding fiction writing: the character one writes has nothing to do with oneself. The choice to make a character do something that the author himself would never do is up to the author himself in the obvious sense, but only within the self-moving real of the fiction to which the author must submit by setting himself aside. The prerequisite for good fiction hinges upon the successful avoidance of the author to impose himself on the story. Here, I’m not saying that good philosophy and good story-telling are the same. The main idea is that we should be careful to not paper over the fact that the site of the vanishing mediation, the singularising function of the subject, erases itself in the process of bringing about a result by virtue of which (seemingly independent) necessity is presupposed.Marx’s response to Hegel founds a similar necessity that is taken for granted, meaning that the subjective decision that lies at its basis is forgotten, disavowed, repressed, lost.7 Similarly, this is how we’re to understand the following quote by Žižek who is thinking this logic apropos the Russian revolution and Lenin:

"A positively existing social system is nothing but a form in which the negativity of a radically contingent decision assumes positive, determinate existence."8

So, not only theoretical edifices but also social systems are of this retroactive nature. Referral to the leader or author can be explicitly pointed out, but this does not at all guarantee that the dimension of the subject as vanishing mediation is recognised. It could even strengthen the obfuscation of the act (or decision) of contingent subjectivity at the foundation. Take Stalinism, which legitimises itself by portraying itself as the continuation of Lenin’s project, turning him into a messianic figure and disavowing the fact that Lenin’s political deeds couldn’t rely on any objective necessity that’d function as a guarantee whatsoever.

Back to Real Speculations. Cadell Last’s history of 21th century spirit that looks at popular intellectuals and superimposes the structure of the Phenomenology could function as the ground for such new necessity as described above. Every external, universal history of thought is unavoidably reflexive. It reveals what singular thought is made up of. Last’s materialist dialectic is undoubtedly singular, i.e. could only be done from the standpoint of a subject. Yet, now that the intrinsic link between these historical figures has been laid bare, we cannot unsee it. Last has erased himself from the picture, but not despite, but because of including the subject(s) within his thought. Hence, the universal history of thought as New Atheist Historicity is grounded in that very paradox of the contingent decision of the reflexive subject which retroactively establishes necessity.

Too often we find thought-inhibiting knee-jerk reactions to Dawkins, Peterson, etc., that aim to downplay their influence and role in the contemporary zeitgeist. Last has succeeded in showing that the role of philosophy is foreign to such condemnations. In that sense, he’s staying true to the philosophical impulse and work that we also find in the contingency of Hegel’s decisions repeated into necessity; the necessarily eclectic nature of speculation. To read out of context, like Last is doing with Hegel and New Atheist historicity is precisely the decision that makes his analysis so powerful. It is ground-breaking by virtue of breaking apart the coordinates of what we assume the context to allow for. To enact real speculations is to write out of context.

But Real Speculations is solely one book on the theoretical side of Last’s project, on the side of praxis, of subjects in a social system, there is Philosophy Portal. This latter being an indispensable part of the systematic social work, the work of the concept, the work of freeing speech grounded in the collective reading of foundational primary sources of modern philosophy, as well as continual exposure to contemporary thinkers, communities and networks.

Both are constituted in Last’s repetitious — backwards circular — decision-making over the years, coming forth from his Christian Atheist service, i.e. his kenotic drive.

Together, Real Speculations and Philosophy Portal are astonishingly invigorating and pioneering projects that show how theory and practice can relate today. These ongoing projects, crystallised in a plethora of medial forms (like conferences and anthologies), show us that we can avoid the trap of theoretical obscurity, while not succumbing to the superego injunction to act (because we can’t bear to sit with our powerlessness and think). Our volatile and suffocating political climate is in desperate need of these projects. While being alert to the trap of growth, especially as it goes into overdrive in our digital realm (in the unsaid name of capital), I do believe that this theory and social interfacing can be impactful and inspirational to culture and society at large. Such projects are beacons of hope against the ubiquitous outsourcing of our subjectivity to AI, which is actively robbing us of the chance to sit and think with our anxiety.

Still, it would be wrong to see Real Speculations as a prescription on what to think or how to act. A glance at the cover of the book reveals it all. The book is meant to be taken in, digested, and flushed down the toilet.

If we can’t bring ourselves up to read out of context, we’ll surely fail to write — I mean shit — out of context. We can be glad that Last is not constipated. What follows now is an attempt of mine to enact some much needed Hegelian shitting.

I am reminded of an anecdote from a friend of mine who visited Russia during the economic crises right after the collapse of the Soviet Union. During his visit in Nizhny Novgorod, he visited the largest library in the city located on Victory Square. My friend bought a ticket to go to the toilet, but when he entered there was no toilet paper to be found… Until he laid his eyes on the sill. There it was: Vladimir Lenin’s Imperialism: the Highest Stage of Capitalism. He opened the book and saw that pages had been torn from it. Could it be? A stack of the same books lay beside it, ready for use. He tore the pages and helped himself with Lenin’s bold analyses. Later on, the lady at the counter informed him that indeed, there was an excess of books by Lenin, but a shortage of toilet paper. She did not laugh.9

We can only hope that if communism is our future, it is destined to collapse, so that a similar fate awaits Real Speculations.

Communisation

In the spirit of Real Speculations we’ll attempt to rethink the notion of communisation. But first, what is the status of speculation today? As Last notes in the preface, the word speculation gets a bad rap. He decides to salvage the term:

“To make speculations real, one cannot simply represent an external antagonism and mobilise it towards one's own interests; rather, one has to embed oneself as self-repelling singularity in the real of antagonism itself, and live out these antagonisms to discover the result in their inner logic.”10

If we could oppose real speculations to anything, in a conceptual manner, it would be the bad infinity that merely asserts outward endlessness in an abstract line. Perhaps in the form of linear progress, a teleology which functions because the goal is forever out of reach, and toward which we are forever condemned to progress. Real speculations are truly infinite because the finite determinations that an author like Last makes are immanent to the disorientation of our epoch without the promise of an abstract beyond. Real speculations have dropped the fantasy of asymptotic motion, the idea that at the end of the day — at the falling of dusk — we have no choice but to strive to unreachable horizons. Real speculations do not impose an abstract universal from without, but run with the immanent antagonism to bring their logic to an end in the singular, like Last has done with New Atheist historicity.

If our political-economic situation is immanently theological and unconscious, if all the figures of New Atheist historicity are all but ideological symptoms of capital as God, what do we make of this God regarding speculation? In his paper on real abstraction, Mladen Dolar takes a stab at the issue. He thinks capital’s infinity in terms of bad speculation:

“The Hegelian speculation was precisely a move that transcended the bad infinity, while the speculation pertaining to capital is like the infinitization of the bad infinity, perhaps not a bad name for the nightmare of our times. Bad infinity raised to the level of bad speculation, the seemingly most speculative moment as the straying away from speculation.”11

I want to propose communisation as a term that doesn’t represent the mobilisation of external antagonisms towards my interest, but as an effort to bring the inner logic of capital as the infinitisation of bad infinity to an end. I do this without the pretension to give an answer or solution to external antagonisms. Inspired by Sic, the now defunct International Journal for Communisation, I hold that the minimal approach of communisation exposes a problematic.12

Communisation is a notion that emerged during the crises of the late 60s and early 70s, originating in the left communist critique of the communist movement. Instead of conceiving of communism as the stage that requires the traversal through the dictatorship of the proletariat and socialism, communisation already exists as the real movement of the liberation of value. Giles Dauvé defines it the following way:

”Communism is not an ideal to be realised: it already exists, not as alternative lifestyles, autonomous zones or counter-communities that would grow within this society and ultimately change it into another one, but as an effort, a task to prepare for. It is the movement which tries to abolish the conditions of life determined by wage-labour, and it will abolish them only by revolution.”13

According to communisers, Marx’s critique of the value-form had practically never been taken up by the communist movement. Democracy in the workplace (e.g. council communism), as well as centralised planning (e.g. really existing socialism) both leave the capitalist mode of production untouched.

More concretely, this notion was an alternative to Marxism-Leninism (e.g. the dominance of the Soviet Union and the European communist parties) and Maoism. Besides that, it was a response to capitalist restructuring:

“In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a whole historical period entered into crisis and came to an end – the period in which the revolution was conceived in different ways, both theoretically and practically, as the affirmation of the proletariat, its elevation to the position of ruling class, the liberation of labour, and the institution of a period of transition. The concept of communisation appeared in the midst of this crisis.”14

The concept of the proletarian agent enacting the sublation of capitalism through its self-affirmation by political conquest of the state was put into question. The proletariat put itself into question. Consequently, the classic communist conception that a proletarian dictatorship would be the ground from which socialism and communism would be constructed was neutralised.

Value-form

To get to the heart of communisation, we have to understand what Marx means by capitalism. We commence with the value-form because he says the following in Capital vol. 1:

“The value-form of the product of labour is the most abstract, but also the most universal form of the bourgeois mode of production; by that fact it stamps the bourgeois mode of production as a particular kind of social production of a historical and transitory character.”15

The term ‘form’ is crucial here. Marx was critical of political economists who took the form of value for granted and went straight to its content, which is labour. Marx was concerned about the form, what it does to the content, or how labour and its products take the form of quantifiable expressions, like commodities and money, which are both prerequisites for the capital-form. Because I’m condensing a gargantuan topic into an extremely condensed article, we’ll start with a simple triad:

Value in-itself (commodity-form)

A product of labor is useful. It has a qualitative use-value. A commodity is a product of labor that also has an exchange-value, which is quantitative. This is the dual character of the commodity.

Exchange-value is not the property of the commodity itself, but is relative to the exchange-value of other commodities. Analogous to gravity, each rock has a measurable weight, but not each rock contains the property of gravity in itself but is gravitational in relation to other entities which have weight. In the same way the commodity does not have exchange-value inside of it, but has an exchange-value in relation to other commodities. The exchange-value of the commodity is an instance of the relations between commodities as carriers of a discrete magnitude.

Value for-itself (money-form)

The abstract (exchange-)value of commodities can only be related to each other by being constituted in a world of commodities through a single expression of an exchange value that is itself not a mere commodity: the money-form.

The commodity-form and its instances (all the commodities) need an external measure in light of which each magnitude of exchange-value is expressed as such. To compare two commodities as carriers of different magnitudes of exchange-value, there must be the quality of exchange-value itself, which logically precedes quantification, this is expressed as money. Money is not the commodity-form that contains both exchange-value and use-value in the same entity (on different planes) but the embodiment of exchange-value as its own use-value.

Hence, the abstract value of commodities is constituted by the money-form, the universal equivalent. The commodity-form of value (in-itself) cannot exist without (i.e. presupposes) the money-form of value.

Value in-and-for-itself (capital-form)

The money-form qua value for-itself ceases to endure on its own accord if it does not ground itself in itself. It is not for-itself insofar as it’s grounded in the in-itself of the commodity and functions to sustain it through circulatory exchange.

Money must become the self-driving force, self-moving value. Capital is the money-form that turns its function of having its use-value in the realm of exchange-value, to its use-value being the redoubled self-serving expansion of itself.

The money-form becomes the capital-form when the use-value of the universal equivalent, the sole quality of value-form expressed in a magnitude of exchange-value redoubles itself. The capital-form has gone from being a means of exchange as money-form to the goal of the circulation of exchanges. Once this inversion sets off, the capital-form subordinates the commodity-form and the money-form to moments of its accumulation.

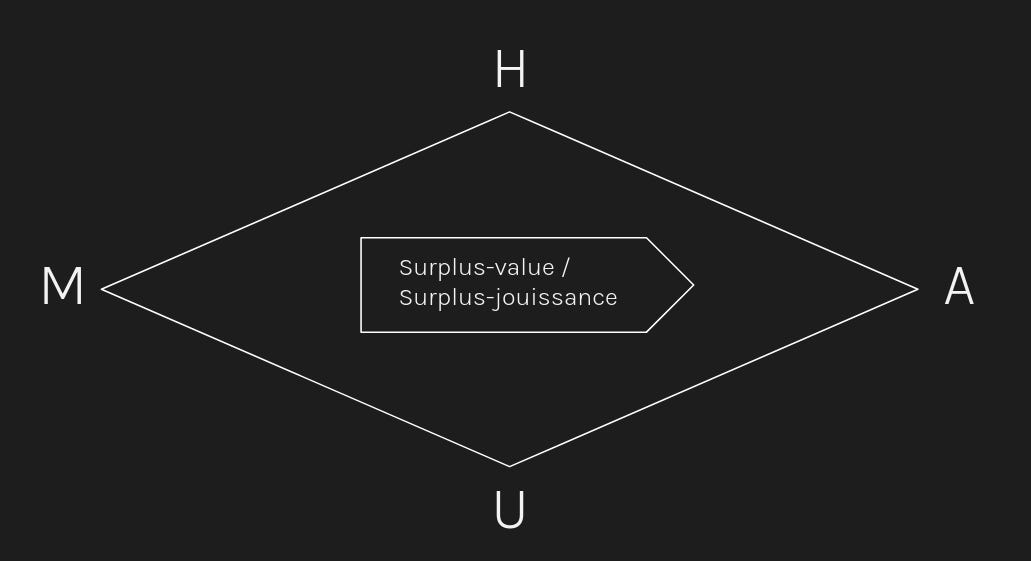

The Marxian formula for exchange circulation as the movement of value in-itself (commodity) and value for-itself (money) is:

Commodity — money — commodity (C — M — C)

With capital, value ceases to be a mere means of exchange but is the end of circulation, exchange-value qua universal equivalent becomes not only the use-value for exchange, but its accumulation is its use-value, value in-and-for-itself:

Money — commodity — more money (M — C — M’)

Now, we grasp the triad of the value-form. Still, the source of value is totally obscure. How does capital’s self-propelling wheel keep turning? In other words: what does its self-driving mechanism presuppose to accumulate itself with? Capital’s presupposition is that it can valorise the content into form. This content is the material world of production itself, namely the domain of humans and nature. Once the shift to abstract labour (quantifiable as value) takes place, capital assumes that it can continue to subsume production for its end. Nevertheless, the formal mechanism of capital is indifferent and blind to the transition from content to form.

Once this process from C-M-C to M-C-M’ is kick-started, it must keep the circulation of value in motion, it must keep exchanging the commodity-form for the money-form and vice versa for its goal: the accumulation of value as capital-form. The alternative is to cease being the end of circulation, which results in a reversion back to C - M - C, or the abolition of the value-form as such. This is how Marx explains the difference between the two formulas:

“The simple circulation of commodities — selling in order to buy — is a means to a final goal which lies outside circulation, namely the appropriation of use-values, the satisfaction of needs. As against this, the circulation of money as capital is an end in itself, for the valorization of value takes place only within this constantly renewed movement. The movement of capital is therefore limitless.”16

Capital, as its own end, comes to itself (M’) to expand itself, which is its end. This exposition of capital as value in-and-for-itself, this abstract self-movement is formal precisely because it is indifferent to the content for its self-continuation. The content of the value-form is labour, which is subsumed by self-driving value in its capital-form.

The question of communism is: how do we go beyond capital as mode of production given that the immediate danger is that we regress to social organisation based on direct domination? What is the alternative to valorising labour with capital as its driving force? The notion of communisation tackles this seemingly unovercomable self-valorisation process. Instead of relegating this issue to the future (after the installment of the dictatorship of the proletariat) it asserts that there must be an immediate shift that abolishes the mode of production based on the value-form and its social relations. In communism, we cease to constitute the value-form because it ceases to constitute us.

Communisation is a process of breaks. It consists of a series of enacting communist measures which are themselves the production of communism. There is a strong link between left communist theoreticians of communisation and Žižek’s rejection of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Even though Žižek never mentions communisation, I argue that we can see him as a communiser. For starters, in the following quote in his his Surplus-Enjoyment:

“Instead of trying to include everything that contributes to wealth in the domain of value, we should strive to liberate more and more spheres from the domain of value.”17

This is communisation, the striving to liberate spheres from the domain of value. Increasingly including more spheres into the domain of value is to support the subsumption of production by the capital-form. If this proposal might seem abstract, the debate on how to recognise forms like domestic work in the household, economically, i.e. value-wise, has been on-going and is still very much alive. Marxism, of course, rejects this route: it rejects the invasion of the capital-form into the family institution.

Let us now for a moment allow ourselves to ignore the political dimension of communism as the revolutionary seizure of power by the proletariat by violent means. Perhaps Marxism could have not accounted for our contemporary situation with all our digital technology spanning the globe, maybe we already have immanent communisation on the level of our global technological civilisation? Maybe Marx was totally correct for his day and age, but what if our technological progress has inaugurated a paradigm breaking shift in the mode of industrial and digital production that Marx and the 20th century communists could not foresee?

Production between value and non-value

Most computers in the world, whether running Android, MacOS or Linux are using free software by GNU, which is supported and closely tied to the Free Software Foundation (hereafter FSF).18 The FSF was founded with the explicit political promise of freedom. In the GNU manifesto, we find a relic of techno-optimism written by Richard Stallman in 1985. According to the GNU project:

“Free software means that the software's users have freedom. (The issue is not about price.) We developed the GNU operating system so that users can have freedom in their computing.

Specifically, free software means users have the four essential freedoms: (0) to run the program, (1) to study and change the program in source code form, (2) to redistribute exact copies, and (3) to distribute modified versions.”19

Back in the day, this sounded both promising and feasible. And it was. It was so viable in fact that even nowadays, GNU still makes up an essential part of a large share of computers. In this sense, the project has been a tremendous success. To ensure the emancipatory goal of the project, Richard Stallman, the main founder of the FSF and creator of GNU says:

“My work on free software is motivated by an idealistic goal: spreading freedom and cooperation. I want to encourage free software to spread, replacing proprietary software that forbids cooperation, and thus make our society better.

That's the basic reason why the GNU General Public License is written the way it is—as a copyleft.”20

Are GNU and the FSF not great examples of liberating spheres from valorisation? Are they not communising projects that make the need for political revolution superfluous? Is this movement not a great example of communisation without being explicitly named as such? The answer is, of course, no. At the end of the GNU manifesto, Richard Stallman admits that programmers will earn less by not being able to sell their software. But, he assures that this compromise is worth it for the future promise. He explains that there’s two main practical reasons to accept this cumbersome fact of a lower salary. First, Stallman argues that sacrificing a high salary in the short-term will yield many rewarding effects for the creativity and freedom of the project, the work is its own reward. In the long term, on the level of the state, a Software Tax can be implemented. This Software Tax would fund the Free Software Foundation and other projects that build our digital commons. He says that this Software Tax might eventually be replaced by a selective voluntary donation. Instead of being taxed by the state and having distribution of the funds based on the current government, one could choose to donate the projects that one supports oneself, which one can legally take credit for as an alternative to the involuntary tax.

The last two paragraphs of the document contain his grand vision. It’s not far-fetched to see it as a version of Fully Automated Luxury Communism. He views the GNU project and the FSF as a step towards post-scarcity society. The beautiful vision reveals thoroughly ideological obfuscation of the political force of capital. Like beer without alcohol, we get communism without revolution.

However, the truth of the FSF does not end there. As is often the case with historical movements intended for emancipation, we find a universalised truth in their betrayal. The universality grounded in the betrayal of the FSF had to pass through it to come into being, but only to subsequently detach itself from it. The new necessity established by the betrayal needed the zealous and ardent activity of the FSF and GNU as the mediation destined to vanish. The word of the murder of free software is open source. This well known term originates in a political disagreement with the principles of the FSF:

“In 1998, a part of the free software community splintered off and began campaigning in the name of “open source.””21

The reason to split off from the FSF was that the name open source is a politically pacified term that can be brought in line with the circulation of capital without scaring off investors, share-holders and the like. Free software’s aim is diametrically opposed to capital subsumption. It is based on the political principle of freedom on the side of production, distribution and the social relations embedded in them. The digital commons were supposed to liberate us. To give an example of the result of the open source software project, let’s take a look at the website of Mozilla Firefox, which is a popular open source browser. On it, they proudly proclaim to be “billionaire-free for 20+ years”. And even though Firefox is considered to be both open source as well as free software, in the terms of its license, it is not at all free from Big Tech. The reason they exist at all is because: "[S]ince 2005, Google's contributed roughly 89% of Mozilla's overall income.”22 There are multiple reasons for Google to invest in Firefox, the main one is to protect its monopoly on browser programs. Even though Firefox is both open source as well as free software, it is one of many examples of a FOSS (free and open source software) project completely subsumed by the valorisation process spearheaded by tech giants. More generally, the paradox of FOSS and non-valorised work show that capital doesn’t only rely on valorisation of production but also on maintaining a dependence on non-valorised labour. In the case of FOSS, it is often at the forefront of digital innovation, and is more often than not eventually subsumed by capital.

There are countless examples of the subsumption of open source projects. It goes both ways: on the one hand, there are initiatives which start out open source and are bought by corporations that close their source code in the process to transition to a proprietary model or discontinue the project;23 on the other hand, there is massive lay-offs within companies which at the same time move initially proprietary model to an open source model, all while making huge profits.24 The reason a company would open source their products is that centralised pieces of software, if they have a large user base, will be maintained by labour that doesn’t fall under the company’s pay-roll, improving the production while reducing the costs. The major difference between the mid-80s and now is that the FSF and the free software movement was not supported by Big Tech. Today, the industry has changed. From Canonical to FUTO, there are serious attempts at breaking up the monopolised space of digital platforms.25 And these initiatives too are led by billionaires. In the case of FUTO, their mission is to reintroduce tech competition based on bringing out high quality products without a hidden agenda. With investment and in-house software development, while setting profit as the primary goal aside, they aim to liberate the tech industry from its current form, the centralised rent-extraction based oligopoly. A noble sounding goal that is welcome because it may have positive consequences for our digital social relations.

In the FOSS movement, there are plenty of examples of developers working on passion projects that are unsupported by billionaires and also without regard for profit. At first glance free software might look like a tremendous communising success of the liberation of human labour from capital valorisation, freeing the means of production. But as should be clear by now, spheres that are ‘liberated’ from value can constitute the other side of the system that keeps value in motion, which doesn’t mean that FOSS, Copyleft or even projects by renegade tech billionaires haven’t achieved positive results or have no emancipatory potential.

The labour required for building and maintaining the code bases that underlie our digital infrastructure is to a large extent socialised and happens on a global scale, while profits or rather cloud rents are privatised. Control and ownership of these means of digital production (called cloud capital) is a decisive factor in the contemporary logic of capital-labour and its class struggle. The digital networks are determinative for our everyday identity, how we act and think, and what we know and don’t know.

In terms of the coming decades, all facts point to political tensions rising and the inevitable increase of censorship along with it. Generally, we are not prepared for an exodus from Big Tech platforms, or, as Yanis Varoufakis calls them: digital fiefdoms owned by technofeudal lords.

A Word on Technofeudalism

Will capitalism ever end? This is a senseless question according to Varoufakis given that it is already in the process of being replaced. However, what has surely not come to an end is the fundamental divide that capitalism relies on, namely the separation between valorised and non-valorised work, which is succinctly formulated here:

”The capitalist drive to produce surplus value is paradoxically both the drive to exploit labour-power and, simultaneously, to expel it from the production process. Capital is impelled by its own dynamic, mediated through the competition between capitals, to reduce necessary labour to a minimum, yet necessary labour is the basis on which it is able to pump out surplus labour. Necessary labour is always both too much and too little for capital.”26

We have already seen that the capital-form as its own end subsumes the labour process. But, crucially, it is also that which distinguishes between itself and its other. Capital posits itself retroactively in a self-differentiated manner containing what it needs to expel within its accumulative motion.27

In his Technofeudalism,

staunchly upholds his claim that capitalism has already been killed. If we take his word on it, can we say that the capital and proletariat logic has reached its apogee? Varoufakis shows that through the mediation of finance capital, and especially since the crisis of 2008, a process responding to the low rate of profit in the world has pushed the development of technofeudalism. The origin of technofeudalism is in the enclosures of the digital commons by corporations which accumulate cloud capital through the extraction of cloud rent, turning its prod-users into cloud serfs. In these fiefdoms owned technofeudal lords, profit is subordinated to a secondary and almost negligible status. Cloud rent is now primary, grounded in the monopoly of digital commons. Instead of corporations monopolising markets, tech fiefdoms replace the markets themselves and emulate them, extracting cloud rent from both profit driven companies which sell the products on the platform, as well as their consumers. AI — I mean sophisticated machine-learning algorithms — are in service of sustaining this technofeudal structure which parasitises on capitalism. Technofeudal fiefdoms were and are still fueled by the way the financial sector and governments respond to capitalist crises. Since 2008, central banks all over the world are continuously printing trillions (the euphemism for which is quantitative easing). Where is all this money going?“The only serious investment of the central bank's poisoned money during this time [from 2008 to 2020] went into the accumulation of cloud capital. By 2020, cloud rents accruing to cloud capital accounted for much of the developed world's aggregate net income. That in brief is how cloud rent gained the upper hand and profit retreated.” (Technofeudalism, Yanis Varoufakis)28

It’s notable that the democratic technosocialist model that Varoufakis proposes to struggle against technofeudalism looks awfully similar to a type of corporate anarcho-syndicalism which he is intimately acquainted with. For a short period, Varoufakis worked for Valve Software, owners of the biggest PC gaming fiefdom Steam, and a Big Tech company which works with a comparable model. Of course, unlike his micro-economic advisory job at Valve regarding the Steam Community Market (neither a market nor a community but fiefdom), Varoufakis is proposing macro-economic reform. He wants the state to command the structures and mechanisms of an economy made up of democratic digital corporations. He is calling for a new overarching technostructure. The problem with Varoufakis’ book is not its vigorous imagination beyond the dystopian technofeudalism that we currently live in, it is also not the fact that he adamantly argues against those who scoff at the thesis and claim technofeudalism is yet another moment of capitalism’s self-revolutionising. The problem in Varoufakis’ stellar book — which I take to be an important contribution to the conversation of communist critique of the left — is his democratism. As Žižek puts it in his Surplus-Enjoyment:

“Badiou’s thesis, which is “scandalous” for liberals, is more current than ever: “Today the enemy is not called Empire or Capital. It’s called Democracy.” What, today, prevents the radical questioning of capitalism itself is precisely the belief in the democratic form of the struggle against capitalism.”29

The petrifying fetish of democracy is the foremost way to keep critique of capitalism at bay. One example of the falsity of democratism (and anarcho-syndicalism): take Valve, even though it’s not explicitly anarcho-syndicalist, this is how its organisational structure is generally (sometimes jokingly) described. Yet, if there’s any one figure in the world PC gaming corporations that stands out from the rest, it’s Valve’s founder and president Gabe Newell, who has constant praise and memes orbiting him. In a podcast where he talks about Valve, Varoufakis says that the open and egalitarian company culture has not had to face economic down-turns resulting in sacrificial lay-offs, which would be the true stress-test of its model.30 Anyhow, what we see in all the GabeN memes is a return of the repressed, namely of the necessity of singular — non-democratic — leadership. Paradoxically, we might describe Valve’s model as organic centralism. There’s the centralism of Newell’s incontestable leadership, which grounds the relatively free and organic cooperation at the company. Anarcho-syndicalism, democratic technosocialism or variants of the democratic workplace don’t oppose or undermine capitalism. What such proposals do is occlude the role of singularity, the key role leaders play in political and social transformation. Without rejecting democratic technosocialism outright, it has to be said that there is no intrinsic value of democracy as a principle.

Moreover, we non-democratic communists should not shy away from critiquing the rampant collectivism at work in the revolutionary left that does not come to terms with the inherent limits of the 20th century movements. Time and time again, collectivism results in a disavowal of singularity, turning the real movement into a realisation of a messianic fantasy led by some figure of a dead father (e.g. Lenin) along with his interpreter (e.g. Stalin) validating, and validated by the letter of People’s History. Analogously, Kirsty Rosenstock has recently portrayed the reversal in the insightful manner shown below. From dictatorship of the proletariat to…

The disavowal of singularity turns into a collectivism of the one. The difference between matador Stalin and his proletarian bull is that the former is aware of the spectacle. Nevertheless, it is done on the behalf of People’s History. “Do not let the bull’s mistreatment be in vain!” those in the crowd tell us. And they are right: only with a matador can the spectacle of collectivism sustain itself.

At the same time, communists have been susceptible to bourgeois individuality which rests on the presupposed possibility of direct free relationality, like monads in a vacuum. But maybe this is only possible in communism outside of the exploitative and oppressive structures of capitalism?

No thanks, we don’t have to choose between collectivism and individualism. And more importantly, the opposition is not symmetrical. Chris Cutrone has pointed out that the popular leftist motto “none is free until all are free,” this red colored bourgeois slogan is the opposite of what Marx says. For him, the liberation of the individual precedes the liberation of the collective. Along this line, I claim that the passage through singular proletarisation is the critical zero-point to which we can respond to either with socialisation or communisation. The former has a plethora of forms on which it can rest to justify itself, like democratic socialism, i.e. worker’s management and redistribution of capital; the latter is the impossible act repeated in distinct communist measures, revolutionary not despite, but because we can’t imagine it. Our horizon is the product of the current mode of production that precludes such an act. Given that there is no gradual transition to abolish the capitalist mode of production — it comes in discontinuous breaks — we can say that each measure will set off from a groundless free fall. Apart from speculating on the weakest and vital links in the chain of world capitalism, we can’t can’t propose specific communist measures because we have no predetermined knowledge of the form of crises to which they will respond, immanently. There’s no standard from which we can measure their impact beforehand. A communist measure might turn out to merely have socialised capital, but it might also be a moment of the production of communism.

Whether or not technofeudalism is the end of capitalism or another metamorphosis of it, Varoufakis has set out the course for possible routes to socialise the digital commons. The question of communising technofeudal relations won’t be democratic, and will also not result in free individuals relating. If anything, they will be voluntarist acts carried out by radical singularities of their own accord. Through singular repetition, grounded in nothing, the universal necessity will be disclosed after the fact.

Can we consider the passage from the capitalist socialisation of (and in service to) technofeudal fiefdoms to communism?

Communisation is…

Communisers like the original left commmunists and Žižek are well aware of the problem that the capital-form relies on non-valorised labour and hinders proposing simplistic solutions for abolishing the value-form. Yet, it should not resign us to either pole of the classical communist antinomy between decentralised worker’s democracy and top-down centralised planning, which are both leaving the role of the value-form intact and unsaid. Are we hopelessly condemned to the all-engulfing valorisation of more and more domains of production and its opposite in service to it? Communisation doesn’t allow for resigning oneself to the temptation to ignore the role of value by throwing it over yonder far out in that hazy future where capitalism will be overdetermined by the political power of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Socialisation, to be fair, has emancipatory potential and can make an invaluable difference to the concrete lives of people, but it can also be — and most likely is — an obstinate foreclosure of communisation as revolution: a sclerotic reaction, counter-revolution.

What problem does communisation have with the dictatorship of the proletariat as the result of the political revolution, as the necessary safeguard against capitalist forces and the precondition to the social revolution that transforms capitalism step by step? If the FSF (like many techno-optimists) want communism without revolution, we can critique contemporary advocates of the dictatorship of the proletariat for wanting revolution without communism. Choose one… and lose both.

Communising measures as iterations of the revolutionary production of communism are not deeds satisfying the demands of labour. That is the job socialising programs. Communisation is not a demands-based struggle resting on the affirmation of the political power of the working class. This affirmation is indistinguishable from an affirmation of capital, the political revolution of the working class is its own inherent limit. It implies counter-revolution at once, working against the production of communism.

Moreover, communisation rejects the progressive approach to communism inspired by Marx’s texts like the Communist Manifesto and Critique of the Gotha Program. But, it also doesn’t succumb to the temptation to depoliticise, or apolitically localise communism in alternative communities or forms of non-valorised production and distribution. So what remains of communism as communisation?

“The work of TC suggests that the radical “way out” implied by value-form theory may be determined by the historical evolution of the capital-labour relation itself, rather than being the product of an ahistorically correct consciousness, free-floating scientific point of view or perspective of critique. The historical perspective on the class relation complements value-form theory. And the sophisticated analysis of capitalist social relations in systematic dialectic and value-form theory can inform the perspective of communisation by offering an elaboration of what exactly this class relation is, and how the particular social relations of capitalist society are form-determined as such.”31

According to the theory of communisation, the dictatorship of the proletariat has no basis because there’s no ahistorical class-consciousness to legitimise its rule on. Instead, we are not the master in our own house, reduced to a perspective without the possibility to raise itself above its historicity. Now, this reflexivity is not reducible to relativism, historicism or defeatism. It is a necessary zero-point. We must assume that for us there are no exceptions outside of the subsumption of the capital-form. There are no external resistances to capitalism that we can resort to. These are the stakes of real speculations tarrying with the bad speculation of capital.

Communisation is informed by the real speculations immanent to the social relations of capitalist society. Instead of the same old regurgitated need for an ‘objective’ class analysis concomitant with the search for a subject-supposed-to revolt, Žižek is an excellent resource on the class relation and the status of the proletariat. What remains of the proletariat once we discard class consciousness and the dictatorship of the proletariat? Žižek writes:

”On this point at least, Marx was right in his critique of Hegel, since he was here more Hegelian than Hegel himself — as is well known, this is the starting point of the Marxian analysis: the “proletariat” designates such an “irrational” element of the “rational” social totality, its unaccountable “part of no‐part,” the element systematically generated by it and, simultaneously, denied the basic rights that define this totality; as such, the proletariat stands for the dimension of universality, for its emancipation is only possible in/through the universal emancipation. In a way, every act is proletarian: “There is only one social symptom: every individual is effectively proletarian, that is to say, he does not dispose of a discourse by means of which he could establish a social link.” (Lacan) It is only from such a “proletarian” position of being deprived of a discourse (of occupying the place of the “part of no‐part” within the existing social body) that an act can emerge.”32

To clarify, the quasi imperceptible shift, to come to know the absolute not only as substance but also as subject — that is proletarisation. The proletariat is no positive pole over against capital qua substance, but its inherently invisible counterpart that can’t affirm an identity in capitalist social relations. Here is what Marx says on the proletariat. It is

”a class with radical chains, a class of civil society which is not a class of civil society, an estate which is the dissolution of all estates, a sphere which has a universal character by its universal suffering and claims no particular right because no particular wrong, but wrong generally, is perpetuated against it; which can invoke no historical, but only human, title; … a sphere, finally, which cannot emancipate itself without emancipating itself from all other spheres of society and thereby emancipating all other spheres of society, which, in a word, is the complete loss of man and hence can win itself only through the complete re-winning of man.”33

To invoke a metaphor: to proletarise is to short-circuit bourgeois ideology. As this quote shows, the result of this short-circuit is not to be in the safe outside of ideology. To the contrary, as we see above, it brings Marx to an affirmation of bourgeois humanism. Here, he reproduces the capitalist fantasy of non-alienation, which itself must be proletarised. You can see the kind of whirling that is engendered. Psychoanalysis rules out that there could be a return to the human after the abolition of the proletariat, but maybe there is the winning of a non-class, non-proletarian subjectivity?

It’s hard to say. Nevertheless, in Hegel’s philosophy there is no such thing as everlasting peace. Civilisation is bound up with its seeming other, i.e. war. So what happened to Marxism, which is more often than not associated with utopianism? In his Critique of the Critique of the Philosophy of Right, Last rightly relates this discussion to the infamous relationship between Hegel and Marx:

“[T]he perhaps unintended result of Marx inverting Hegel’s phenomenology and logic like this on the basis of Hegel’s politics, is that those who do not seriously tarry with Hegel’s phenomenology and logic (either because it is too difficult, or because of Marxist presuppositions about it being bourgeois ideology) end up being unable to work on the level of the working class from the perspective of self-relating negativity. Here we have the negative tendency in Marxism towards the self-utopianisation of the working class as capable of realising a non-alienated state of being, instead of seeing the working class as capable of realising itself as the becoming-other of alienation itself.”34

In psychoanalysis, self-related negativity is radicalised to the notion of the death drive. When Žižek claims that we must go through Lacan to be a Marxist today, in my view, it means that our choice is to betray Marxism in two ways. Either, we do what Marx said in the above quote and state that communism will be a return to the exuberant vitality of the human, a renewed basis for the uninhibited flourishing of creative labour. Or, we take serious Marx’s saying that in communism, work/production is “not only a means of life but life's prime want”.35 In other words, we double down on the death drive on the level of political economy (work as want), meaning that think the knots of the capital-form’s production, as the opening to a mode of production in which desire’s shift towards the drive are produced or facilitated by communist measures. Whereas means and want are separated in desire (striving at a distance from its goal), they are unified in the drive (the end is to circle around the missed goal). At worst, socialisation functions as the stop-gap to proletarisation. Solely from repetitious retreats to the proletarian non-position can communist measures be enacted. Proletarisation calls forth the revolutionary act; it calls forth the impossible. For Žižek, this is the Leninist approach needed more than ever today, exemplified by Lenin’s text On Ascending a High Mountain:

"[Communists] who do not give way to despondency, and who preserve their strength and flexibility 'to begin from the beginning' over and over again in approaching an extremely difficult task, are not doomed (and in all probability will not perish)."36

There’s no positive identity of the proletariat, there’s no way to oppose it to other objectively existing classes. Rather, the proletariat is a symptom. In my recent presentation called The Truth of Communism, I’ve tried to express this by stating that there is a non-class society.37 Bourgeois ideology obfuscates class struggle, that is true. It argues that there is no such thing as a class society but a society of free individuals that by rational self-interest choose to enter into egalitarian economic contracts. One is not a communist by calling out the fantasy on which capital relies, the presupposition of infinite growth/expansion. What a communist does is call out the most concrete contradiction between capital and proletariat. Yet, value-form is not something that a communist can distance himself from practically: we don’t exit capitalist relations by calling out the illusion that drives it. The first thing ideology claims is that it is outside of ideology. Our ideology is in what we do, how we relate and are produced by capital. As a good old left communist puts it regarding the bourgeois ideology assigning the primacy of labour over against capital:

”While it seems true and politically effective to say that we produce capital by our labour, it is actually more accurate to say (in a world that really is topsy turvy) that we, as subjects of labour, are produced by capital.”38

And to paraphrase Žižek: precisely this assertion of political effectiveness and labour’s primacy over capital is the capitalist fantasy par excellence. It is a bourgeois capitalist fantasy in the form of a communist heresy. Regardless of whether we point out that there is or is not a class society, we act as if there is not. Capitalism not only alienates us, but also sustains itself with the illusion that we can liberate ourselves from symbolic alienation, that we can be in control of our symbolic universe. Nonetheless, just like we must take responsibility for the unconscious, we are to take responsibility for our capitalist alienation… In past historical movements, it has taken the form of attempts at the management of capitalist economies in the name of the working class and its vanguard party. The history of the communist project has shown that communists can either be very effective at facilitating capital and its industrial modernisation… or not, which is a classic left communist point:

"Marxism as ideology served the non-Marxian practice of transforming Russia into a modern capitalist state."39 (Paul Mattick, 1962)

So do I claim that Marx’s purely theoretical insights have nothing to do with Leninism, Stalinism and Maoism? Not at all. Marx himself was tremendously ambiguous on what to do politically, especially regarding his insights on the value-form. His politically prescriptive remarks, like in the Critique of the Gotha program, seem to lend themselves to a view that gives up on the criticality of the value-form in the communist movement. In a personal communication,

pushed back on me on this point, arguing that a proletariat which manages capital is the first step to take responsibility for it.To understand what type of role the proletariat has in relation to capital, let’s take the following quote by this left communist author:

“For the proletariat to recognise itself as a class will not be its ‘return to itself’ but rather a total extroversion (a self-externalisation) as it recognises itself as a category of the capitalist mode of production. What we are as a class is immediately nothing other than our relation to capital. For the proletariat, this ‘recognition’ will in fact consist in a practical cognition, in conflict, not of itself for itself, but of capital.”40

To use Hegel’s words: proletarian subjectivity is “pure self-recognition in absolute otherness.”41 It is recognition of capital’s conflict with itself. The dictatorship of the proletariat, the affirmation of the worker’s state, is thus primarily grounded in facing that the proletariat is responsible for something it is not in control of, the capital-form as M-C-M’. That is why Cutrone explains that there are two steps to be made here: two steps in overcoming the ‘double fetish’ of capital. To use an old example, labour vouchers can bring us to the recognition that socially necessary labour time is a quantification made possible by the dual character of the commodity in line with M-C-M’. Second, once we have brought out commodity fetishism by making it explicit with such socialising policies (making everyone a worker in a system with democratic workplaces while the state takes over central command of capital), the discrepancy between the bourgeois social relations and industrial forces of production manifesting in the division between capital and labour will become apparent in a way that has not been possible prior to the worker’s state. In short, we go from capitalism through socialism to communism, facilitated by the dictatorship of the proletariat, which, at the moment of ascending to power, merely takes hold of the capitalist mode of production. What is wrong with this?

As we can learn from history, the dictatorship of the proletariat can mean prohibiting worker’s strikes, crushing them if necessary. Here, I’m not saying that historical examples (like the tragedy of the Kronstadt Rebellion) are evidence of the Bolshevik’s authoritarian falsity, but to the contrary, an exemplary case of the explosive negativity inevitable in a struggling ‘worker’s state’. So instead of rallying against Lenin and the Bolsheviks, it is here that we should return from Marx to Hegel… Perhaps here we should juxtapose communisation to the dictatorship of the proletariat on the level of Hegel’s triad of the ethical system. As Last notes in Lacanese, Marx’s reversal of Hegel in his Critique of the Philosophy of Right claims the state is imaginary whereas the family (as first moment of the ethical system) is real:

“Marx wants to force philosophy into a practical politics that centres the material conditions of Real man, and specifically the Family and Community (or civil society). Of course, in this forcing, he is not asking us to consider the material conditions of any Family or Community, but as mentioned above, the Families and Communities that comprise the “working class”, or the “proletariat”, which he sees as the material basis for a new civil society which re-organises the principle of society itself. This proletarian Family and Community is not exactly equal to the peasantry of pre-capitalist, pre-industrial society, but rather is actively produced by capitalist and industrial conditions[.]”42

The state is imaginary whereas the family is real, for both Hegel and Marx community, is reserved for the symbolic. Are we skipping over the family and community if we take the capital-labour logic to be a problem relegated to the socialist construction in the dictatorship of the proletariat? Has Marxism properly thought its relation to Hegel’s ethical system and its triadic partitions?

Where do we start? Hasn’t capital taken hold of each moment of Hegel’s ethical system?

I’m proposing to think the role of the big Other and jouissance in the real of capitalist socialisation, proletarised to the point of calling us upon the act of the communist measure in all three facets of the system. Can the social revolution come before, or coincide with the political revolution? And if we have an answer to that question, what is the nature of the question to which we are responding? In other words, whatever the answer is, in regards to which moment of the triad are we thinking it? Without having to disregard the painfully intractable problem of the state that the term ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ points to, we can’t and shouldn’t return to it as it as a stop-gap which, in favour of collective self-affirmation, risks to forego the equally — if not more — intractable problem of family and community. That is what proletarised communisation might help us to think. The singularity of the act; the contingency of the communist measure; the opacity of our symbolic alienation; the proletarian family; these are all questions which proletarisation discloses for communisation to address.

Revolution as communisation doesn’t resolve these issues, as of now, that is what capital does, destroying itself in its wake. Communisation is the production of communism within and against the capital-form, immanent to its crises and class struggles. Communist measures, as simple measures by the proletariat within the class struggle produce the class belonging as an external constraint, a conflict of capital, which is what it abolishes. It does this not as momentary, territorial gains, but the production of communism as the struggle against capital: the struggle of the proletariat against its own constitution as class that is not a class. It’s own class character is capital, it is the limit of its action. The communist measure turns the proletariat against itself. The revolution is universal abolition of the proletariat. Revolution brings about its own counter-revolution. Is proletarisation of capital the struggle of communisation as communism? If that would be the case, we wouldn’t be able to distinguish communism from capitalism.

The simultaneity of communism’s production resides in the fact that communisation is not a promise that is yet to be realised, not a possibility that we are getting closer and closer to but dissipates as soon as we clasp it, but the real movement that doesn’t even seem to exist. Because perhaps it doesn’t. Regardless, we can’t simply assume that it does. Communism is not an abstract standard against which we measure the capital-labour relation, it is the impossible call which the proletarian subject decides to heed by virtue of its inexistence as a fully constituted class in capitalism. Communism does not complete the proletariat as a class, but terminates its spectral constitution as a non-class by universal abolition of the valorisation of labour and the divide between classes as such.

In the Critique of the Gotha Program, Marx delivers scathing critique of the labour as the source of value (capital circulation) and other tenets put forth by the program. He proposes the continuation of bourgeois right after the revolution through the use of labor vouchers, a wage without the deduction of surplus by capital. He says that:

“Between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.”43

Marx never published this text during his life. Today, it leaves the most important questions open at best, and leaves us fixated with orthodoxy at worst. Instead of relegating the issue of the immediacy of the communist measure as the act of the transition from value-form to its abolition to the future, communisation faces up against the immanence of the logic of capital-labour by having its zero-point in proletarised subjectivity. Throughout the 20th century, from early on up till now the left communist current pointed to something that merits to be repeated today:

"Today, all attempts to re-establish the Marxist doctrine as a whole in its original function as a theory of the working classes social revolution are reactionary utopias."44 (Karl Korsch, 1950)

There is a non-class society.45 This is what dogmatic Marxisms disavow. Lodging the problem into the future, appealing to the notion of class-consciousness and the dictatorship of the proletariat is part of the problem that point to a return back from Marx to Hegel. Usually, dogmatic forms of communism reproduce the fantasy of the imaginary mastery over our fate with a non-alienated horizon.

With proletarisation as a type of subjective destitution toward the unconscious qua self-related negativity, I’m attempting to think the shift from forms of intentional and explicit communist identity, to a mode of jouissance that is not reducible to a language and can withstand a multiplicity of differentiated identities because they rendered irrelevant in the singular act of communisation. Proletarian subjectivity is the non-dialectical core, the zero-point of the drive. That is the heart which constitutes communisation, the production of communism through the establishment of communist measures in conflict with capital. Or, to put it metaphysically: communisation is the repetition of radically contingent decisions by subjects repeated into universal necessity.

Proletarising Marxism means letting go of the ‘ahistorically correct consciousness’. Class consciousness, this imaginary figment upon which political activity tends to be based, is reactionary because it lends itself to the refusal to pass through the necessity of capital’s total subsumption. The working class is not the exception to capital. We start off from the totalisation of capital and its points of immanent failure outside of which there is nothing. There we find the proletariat which in its self-abolition might — we can’t be certain — produce communism.

Far from being a way to retract into obscurity, it is the fixation on the right (meaning imaginary) ahistorical insight in the name of ‘class consciousness’ and the dictatorship of the proletariat that leaves aside questions of the immediate abolition of the value-form in the act of communisation.

So, communism without revolution, or revolution without communism? To paraphrase our favourite Stalinist Žižek, they are both worse. Both are markers of capitalist alienation and the fetishisation of supposedly impending non-alienation. Both must make way for a ruthless proletarisation of all that exists. In the words of Paul Mattick, from whom this notion is inspired:

"For Korsch, all the imperfections of Marx’s revolutionary theory which, in retrospect, are explainable by the circumstances out of which it arose, do not alter the fact that Marxism remains superior to all other social theories even today, despite its apparent failure as a social movement. It is this failure which demands not the rejection of Marxism but a Marxian critique of Marxism, that is, the further proletarisation of the concept of social revolution."46 (Paul Mattick, 1962)

Marxism today requires a merciless and thorough betrayal of its own thought and political action — that is proletarisation. The immanence of our theopolitical-economic situation is already imposing radical measures for the perpetuation of the capital-form, especially on the level of fictitious capital and cloud capital. The deadlock expressed in proletarised subjectivity calls for its response by communist measures. Here, before heading deeper into the weeds of the value-form, let me clear up the basic gap from which I’m operating. It is situated in the assumption of communist theories (about communisation or else) which, like Žižek puts it, don’t enact the return from the idealist Marx to the materialist Hegel:

”[I]n a way, Hegel was closer to the mark than Marx, the twentieth‐century attempts to enact the Aufhebung of the rage of the disenfranchised masses into the will of the proletarian agent to resolve the social antagonisms ultimately failed, the “anachronistic” Hegel is more our contemporary than Marx.”47 (Žižek, Less Than Nothing)

Even though I’m tremendously appreciative of the left communist speculations, time and time again — without exception as far as I’ve seen — I keep coming up against the motive that communism is non-alienated. It’s mainly visible in the form of humanism and gender abolition which function as stop-gaps to think the concrete rituals of community and family, which psychoanalysis works through with concepts such as unconscious enjoyment, the big Other, and sexuation.

No communism without psychoanalysis means that we can no longer afford to think its production without proletarisation as symbolic castration, which is not merely human or dialectical, but silent in the repetition of the drive.

Žižek’s concept of communism differentiates itself in these two aspects: (1) the return from Marx to Hegel, and (2) a Marxism that has thought through the consequences of the psychoanalytic paradigm. To simplify to the utmost: the former is exemplified by war communism, the latter by the death drive.

The Non-All of Absolute Capitalism

Just after Žižek’s above-quoted passage proposing the liberation from value, he turns around and writes:

“However, this in no way implies that we should simply exclude more and more domains from the sphere of valorization. Valorization could and should also be exploded “from within,” by way of exploiting the paradoxes and unexpected results of the inclusion of new spheres in the process of capitalist valuation.”48

What does this mean? To unpack this jarring reversal by Žižek, I will invoke the notion of absolute capitalism. The reason I’m making use of this term here is twofold:

If capitalism has already been replaced by technofeudalism, it had to pass through the conceptual peak of total subsumption, which is what absolute capitalism denotes;

If this is not the case and technofeudalism is a mere moment of capitalism — I won’t give a definitive answer in this article — then, it is not simply capitalism, but capitalism that is caught up in its own loop of total subsumption (explained below).

Besides, the speculative connotation of the Hegelian term ‘absolute’ points to both the zenith of a concept, as well as its letting go, or release; its comprehension as well as absolution. Communisation is to be thought within the paradox of absolute capitalism. As we have seen, the logic of capital-labour precludes the endorsement of proletarian autonomy as a site of positive resistance. Or, taken in a more general sense, it precludes the search for a subject-supposed-to-revolt-for-us, whether that is the working class, Palestinians or LGBTQ+. We pass from Lacan’s masculine logic of the All (capital) and its Exception (resisting identities and collectives) to the feminine logic of the non-All, as indicated here by Žižek:

“A nice example of Hegel’s insight into how the Absolute always involves self-splitting and is in this sense non-All: with the production of the workforce itself as a field of capital investment, the subsumption under capital becomes total – but, precisely as such, it becomes non-All, it cannot be totalized, the self-referential element of the workforce itself as a capital investment introduces a gap which introduces imbalance into the entire field.”49

To reiterate, the proletariat is a symptomatic knot of the class struggle of the logic of capital-labour. The proletariat is not a positive sociological category, but the expression of the fundamental cut in the social edifice regarding the logic of capital-labour. In other words, there is no ‘proletarian exception’, no fully constituted working class identity over against capital. The proletarised subject merely takes cognisance of capital’s antagonism and its actual forms. Proletarisation is hystericisation. Communisation, then, haunts us in the interruptions of the compulsion of capital. In what follows, I will show that with total subsumption, the hystericisation of capital’s self-conflict is brought to its extreme, to what Lacan calls the logic of the non-all without exception.

Formal, Real and Total Subsumption