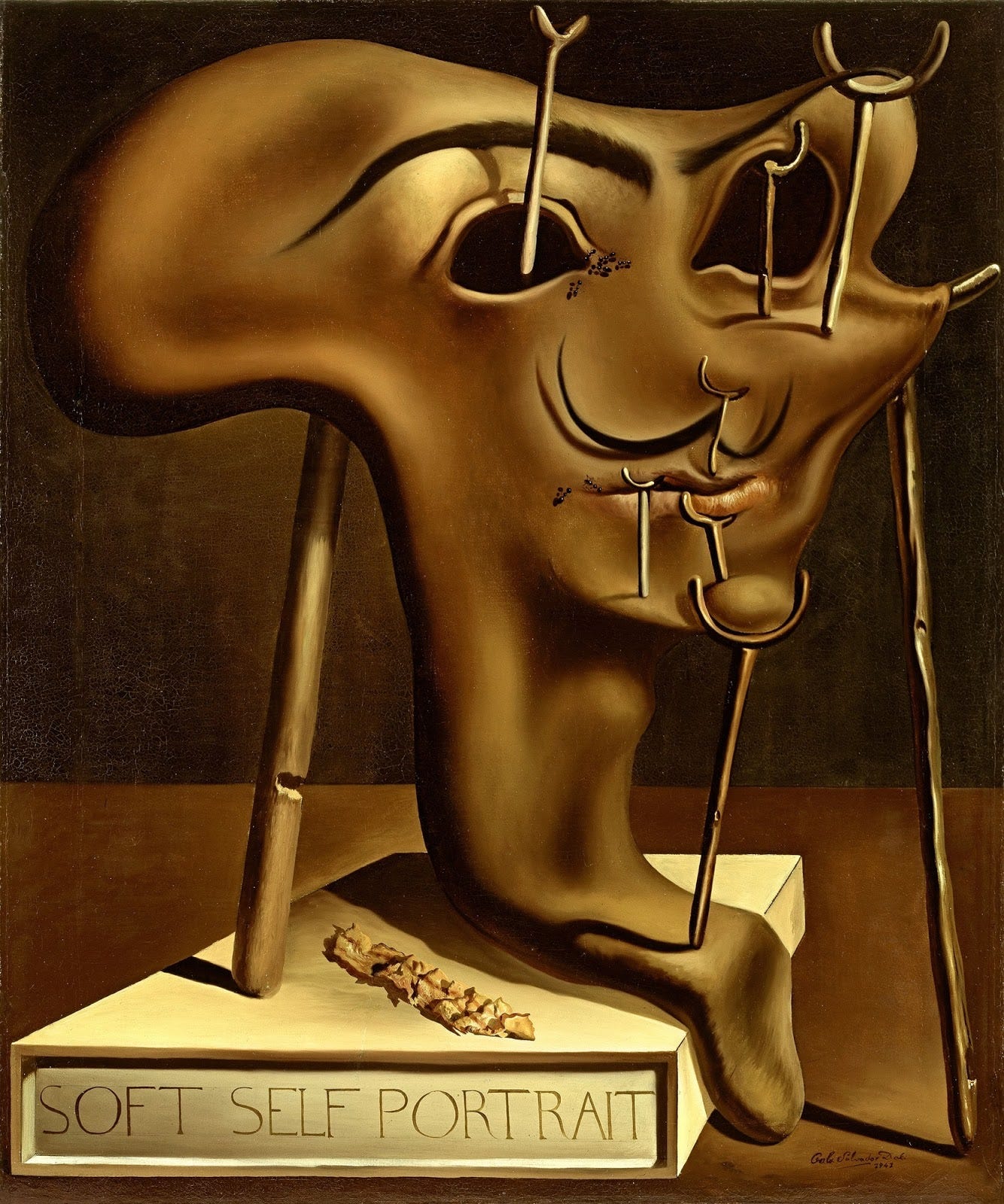

The "I" as a Funny Circle

Inspired by my reading of specific passages in the Science of Logic, in which Hegel writes on the concept, or the "I", and critiques Kant for his inability to hold fast to its funny movement.

A year ago, I started venturing into an attempt to think the “I”, mainly being inspired by its dialectic as explicated by Hegel in his Phenomenology of Spirit. You can find the article here.

The Determinate Concept & The Concept as Determinate

Among the many concepts in Hegel’s Logic, it would have to be said that the concept itself, is its foremost concept. The whole third part of the Science of Logic, that is, the Doctrine of the Concept is dedicated to it. The Doctrine culminates in the truest and most beautiful blossoming of the concept, the Absolute Idea. But how are we to start understanding the concept? First of all, we would have to rid ourselves of the presupposition that Hegel is talking about the concept as something that we have, as in, ‘I have the concept of a thing’. Surely we can have concepts of things, though for this he reserves the name ‘determinate concept’. It is something different from the pure concept as determinate;

“The concept […] is none other than the “I” or pure self-consciousness. True, I have concepts, that is, determinate concepts; but the “I” is the pure concept itself, the concept that has come into determinate existence.”1

The way in which we are to think the “I” philosophically, is firstly to abstract from and set aside any arbitrary phenomenal associations we might have with it. What is the “I”? Well, if you’ve successfully abstracted it from any associations, it would have to simply appear as a determinate concept, but then again, we’d be reducing it to the presupposition that it is something that I have… From there on out we could argue that the “I”, insofar as it is a determinate concept or insofar as we have it, is a contradiction, one which is a kind of self-contained, recursive loop (the “I” is that which has the “I”, which is that which has the “I” ad infinitum). It is evident that ‘having’ the concept of the “I”, shows that there’s no immediate self-equality, no immediate identity of the “I” with the “I”2.

To give an example of what is occurring here using an analogy; I am not my body, I have a body. Therefore, I am more than body, or perhaps less than body. Either way, insofar as I have anything, I am not immediately identical with it. Strictly the same logic is occurring with the “I” having the determinate concept of the “I”. If we hold on to this thought and accept that the “I” might be something to be had, as a determinate concept, we’d have to inquire into what this “I” ‘that I have’ is, as such. Full stop. We know it at least not to be the same as the former “I” which is having it, as we’ve seen above. It’s neither your singularity (as the “I” to yourself), nor mine. It is in fact neither… However, this “I” having a negative relation to both our “I”’s, does not become completely meaningless. We could all principally have this “I” (or determinate concept thereof), and this is a commonality to all. It has constituted itself as a (negative) universality. As Hegel will put it, the “I”

“[…] is universality, a unity that is unity with itself only by virtue of its negative relating, which appears as abstraction, and because of it contains all the determinateness within itself as dissolved.”3

Is dissolved? How so? Because it denotes nothing of the sort that we’d imagine it to denote, that is, the “I” as I am, the singular “I”. So, apart from the universal “I”, there’s another one;

“In second place, the “I” is just as immediately self-referring negativity, singularity, absolute determinateness that stands opposed to anything other and excludes it — individual personality.”4

The “I” is both the singular “I”, which I am, and at once the “I” of universality. Do I have this latter “I”, or am I this “I”? We’d have to say that in our negative relating to the “I”, I am not this “I”, nor do I have this “I”, but am its exclusion, its negativity. The singular “I” is by neither being nor having the universal “I”. In it, I refer to negatively as affirmative. And this, the “I” as being its own not-having, or being that which is negatively related to itself, and only in this referring truly and singularly being itself, is the perishing which equals its abiding (as I’ve attempted to bring out in my former article on The Dialectic of the 'I').

I am I, and in this claim, I have already implied there to be a distance to the “I” insofar as I am able to relate subject to predicate in judgment. Either way, having the “I” as a determinate concept, or judging the “I” to be “I” amount to it being self-referring negativity. But what about the relation of the universal “I” to this negativity of the singular “I” in their difference? To that, I will say that I speak of “I”. And in this preceding sentence that relation and difference should already be apparent. The former I simply denotes the singular me, the latter “I” denotes the universal “I”ness, common to us both, or, which is the same, uncommon to us both as it has not much to do with our singular “I” at all.

It might seem as if I’ve made a mess, I know. The “I” has fallen apart into two, the universal “I” and the singular “I”. Though the story does not end here, there’s a third that holds together this mess. For the “I” abides in this mess, I abide in it, am unperturbed by it. As a matter of fact, “I” am “I”. “I” equals “I”, and there’s nothing any mischievous dissection can do about it. The unity persists, and is not opposed to the “I” equaling itself, for the “I” contains it. As Hegel says:

“This absolute universality which is just as immediately absolute singularization — a being-in-and-for-itself which is absolute positedness and being-in-and-for-itself only by virtue of its unity with its positedness — this universality constitutes the nature of the “I” and of the concept; neither the one nor the other can be comprehended unless these two just given moments are grasped at the same time, both in their abstraction and in their perfect unity.”5

For Hegel, the concept is the “I”, and the “I” is the concept. That much is clear. Now, the “I” as an object of thought, or universal concept, is not simply opposed to the “I” which I am, and we fail to comprehend the “I” if we cannot apprehend the persistence of the “I” as and through this self-opposition which collapses into a oneness, an identity inclusive of its difference, that is, a being-in-and-for-itself that not only is as such, but also posited by the “I”.6

The Objective Concept and Language

As we’ve seen, the “I'“ is a negative unity, a third holding two disparate elements such as the singular “I” and the universal “I” together, containing them and consequently cohering as a singular-universality. This idea of the “I” functioning as a unity as well as the “I” being the concept, goes back to Kant according to Hegel7. Of course, the “I” as a unity is confronted by numerous phenomena, extended in space as well as in temporal succession, and it cannot lend its unity from these scattered appearances. The name of that which the “I” does have a simple self-reference to in being constituted, is the object.

“— the object, says Kant in the Critique of Pure Reason (2nd edn, p. 137), is that, in the concept of which the manifold of a given intuition is unified. But every unification of representations requires a unity of consciousness in the synthesis of them. Consequently, this unity of consciousness is alone that which constitutes the reference of the representations to an object, hence their objective validity, and that on which even the possibility of the understanding rests.”8

The manifold of intuitions, or different sensory impressions are disparate, but unified by the concept or the “I”, constituting them as an object. It is on the side of the “I”, or the unity of consciousness as a synthesis that objectivity lies. Not, as pre-Kantian philosophies might have it, lying out there over yonder, as a substance apart from and self-constituted independently of the “I” or concept.

“On this explanation, the unity of the concept is that by virtue of which something is not the determination of mere feeling is not intuition or even mere representation, but an object, and this objective unity is the unity of the “I” with itself. — in point of fact, the conceptual comprehension of a subject matter consists in nothing else than in the “I” making it its own, in pervading it and bringing it into its own form, that is, into a universality which is immediately determinateness, or into a determinateness which is immediately universality.”9

The unity of the “I” and its object, or the concept and its objectivity, is in both cases contained by the former. The “I” is opposed to its object, and since this object is only constituted by the “I”, it is the unity of the “I” itself that self-externalized this object within it, since this object itself has come from it, is not taken from the outside. The object is, only as mediated by the concept. Wherever we find jumbled up feelings or representations, or disunity, it is by thought that the “I” can mediate them and unify them into its own objectivity. This is not the same as the “I” enforcing its own singular and unique appropriation, but universal conceptualization. By diving into a subject matter, or an object of thought, we make ourselves one with it, and let its objectivity be in a unity of the concept’s singular-universality.

An example: when starting to learn a new language, it always looks as if the grammatical rules are arbitrary, and that the spelling of words is random. To make a new language one’s own, one is to be pervaded by it, and to study it for an extended period. Over time, the seeming abstractness of its universal grammar, and the seemingly unconnected and contingent idiosyncrasies of the language will cohere and be integrated. To put it in Hegelese: the universality and singularity will become simultaneous in the form of the “I” and its objectivity. At that point, one does not have to think consciously about its grammar, does not need to think about what word has to be used in what context, one spontaneously speaks ones determinateness universally. There’s an objectivity to the newly acquired language, but only as the “I” has made itself one with it, has made it its own, has unified itself with it, not by imposing its associations, but by letting the object of thought, the subject matter of the language run its own course in one’s studies. This goes for all conceptual subject matters that one wants to think and become proficient in. In the next passage, Hegel goes into a bit more detail as to the process of conceptualization:

“As intuited or also represented, the subject matter is still something external, alien. When it is conceptualized, the being-in-and-for-itself that it has in intuition and representation is transformed into a positedness; in thinking it, the “I” pervades it. But it is only in thought that it is in and for itself; as it is intuition or representation, it is appearance. Thought sublates the immediacy with which it first comes before us and in this way transforms it into a positedness; but this, its positedness, is its being-in-and-for-itself or its objectivity. This is is an objectivity which the subject matter consequently attains in the concept, and this concept is the unity of self-consciousness into which that subject matter has been assumed; consequently its objectivity or the concept itself is none other than the nature of self-consciousness, has no other moments or determinations than the “I” itself.”10

The concept has objectivity in and for itself, beyond appearance. What does this mean? Another way to put it is that I am united with myself in the relation I have with an object of thought. The for-itselfness, or the fact that my relation to an object is my own relation to myself, as both are within the same concept, does not take away its universality, the concept that posits its very objectivity, can only have this in itself of the universal object as a for itself of the singular “I”.

Like Kant, Hegel finds the non-"I” to be within the “I”. This begs the question — what is truly out there, beyond everything which is the “I”? For Kant, this is the thing-in-itself, unbounded to any for-itselfness, uncontained by the “I”, completely and utterly removed from it, a concept denoting solely the unconceptual. For Hegel, this in-itself, is simply another determination of the “I” itself in its abstract universal form — nothing but an empty representation.

The “I” as Representation Void of Concept

In thinking the “I”, we should be careful not to reduce the “I” to a representation of it, or what we might picture it to be.

“Accordingly, we find in a fundamental principle of Kantian philosophy the justification for turning to the nature of the “I” in order to learn what the concept is. But conversely, it is necessary to this end that we have grasped the concept of the “I” as stated. If we cling to the mere representation of the “I” as we commonly entertain it, then the “I” is only the simple thing also known as the soul, a thing in which the concept inheres as a possession or a property. This representation, which does not bother to comprehend either the “I” or the concept, is of little use in facilitating or advancing the conceptual comprehension of the concept.”11

The “I” does not have the concept. The “I” is the concept. To revert to a representation of the “I” that has the concept as some kind of all-encompassing still-point that contains the concept as movement within itself, fails to include the “I” itself, and the dialectical convulsions its movement consist of as itself the concept as such. Kant with his empty representation of the “I” fails to comprehend this, since

“[Kant] fixes on how the “I” appears in self-consciousness, but from this “I”, since it is its essence (the thing in itself) that we want to cognize, he removes everything empirical; nothing then remains but this appearance of the “I think” that accompanies all representations and of which we do not have the slightest concept. — It must of course be conceded that, as long as we are not engaged in comprehending but confine ourselves to a simple, fixed representation or to a name, we do not have the slightest concept of the “I”, or of anything whatever, not even of the concept itself.”12

Along with all representations that we have, there is the “I”. It seems to stay self-similar in all, encompassing all, without being effected by whatever it contains. This is not actually a conceptual grasp of the “I”, but an abstract representation of it. And as I think, I might want to reduce this “I” to a means to think the “I”, as if I could be my own means. This again, takes the “I” to be a representation. It is a stoppage of thinking. Since it blocks the inclusion of the “I” into itself as movement, as conceptual. It takes the “I” to be something that could stand above and beyond itself as a fixed point, as detached from anything that it contains.

“— Peculiar indeed is the thought (if one can call it a thought at all) that I must make use of the “I” in order to judge the “I”. The “I” that makes use of self-consciousness as a means in order to judge: this is indeed an x of which, and also of the relation involved in this “making use,” we cannot possibly have the slightest concept.”13

It’s not that I make use of the “I”. I am the “I”, the concept, pure self-consciousness. The “I think” that accompanies representations seen as a fixed point halts the thought of it. The idea that the “I” is a means, is subsequent way in which this representation of the “I” can stop us from thinking the “I” for itself, on its own terms, as a unity of its self-contradiction. A metaphysics that relies on a representation of the “I” as a kind of meta-perspective outside of what it contains, that rejects the comprehension of its logical moments as a unity, reveals something spiritual about the very “I” proclaiming it.

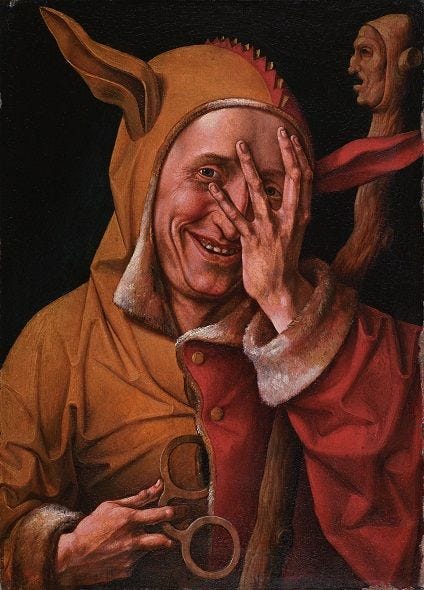

Laughable Awkwardness

In the following passage, Hegel will make an appeal to Kant feeling awkward about the weird movement of the “I”:

“But surely it is laughable to label the nature of this self-consciousness, namely that the “I” thinks itself, that the “I” cannot be thought without the “I” thinking it, an awkwardness and, as if it were a fallacy, a circle. The awkwardness, the circle, is in fact the relation by which the eternal nature of self-consciousness and of the concept is revealed in immediate, empirical self-consciousness — is revealed because self-consciousness is precisely the existent and therefore empirically perceivable pure concept; because it is the absolute self-reference that, as parting judgement, makes itself into an intended object and consists in simply making itself thereby into a circle. — This is an awkwardness that a stone does not have. When it is a matter of thinking or judging, the stone does not stand in its own way; it is dispensed from the burden of making use of itself for the task; something else outside it must shoulder that effort.”14

What’s so funny? The viciousness of the circle. For Kant, however, it feels so awkward that he avoids and shies away from its truth. The truth that gets at the very essence of self-consciousness, the thing-in-itself. Stones aren’t awkward at all, because they have no way of stubbornly rejecting to be thought, they don’t have the freedom of spirit to think against themselves or deceive themselves, to be internally opposed to themselves in self-determination.

To clarify in some preceding points; does or does the “I” not make use of itself in thinking the “I”? Yes, and no. It does insofar as the hiccup in thinking the “I”, the absolute self-reference that thinks an intended object and turns around to itself, is apprehended as an existent unity of its self-contradiction. It does not if the negativity of its self-relation, the opposition the “I” has to itself, is taken as a meaningless and tautological fault. This latter, Kantian, way to ‘think’ the “I” stops short at the fixed representation and terminates the movement of thought as soon as it comes up against the quirky hiccup. For Kant, the circle is awkward and untrue. The “I” as a static representation is his final word on it. This representation of the “I” that floats above paradox and is thought of as that which uses the “I” as means, is one-sided. Kant stumbles upon the quirky circle with its hiccup, and finds the break of smoothness irking and awkward. Kant cringes at the thought of the “I”. For he cannot bear the fundamental truth of the “I” to be dissolving, and the dissolving of this dissolving to be its abiding, as a weird circle, as subject and object.

“The defect, which these barbarous notions place in the fact that in thinking the “I” the latter cannot be left out as a subject, then also appears the other way around, in that the “I” occurs only as the subject of consciousness, or in that I can use myself only as a subject, and no intuition is available by which the “I” would be given as an object; but the concept of a thing capable of existence only as a subject does not as yet carry any objective reality with it. — Now if external intuition as determined in time and space is required for objectivity, and it is this objectivity that is missed, it is then clear that by objectivity is meant only sensuous reality. But to have risen above such a reality is precisely the condition of thinking and of truth.”15

The problem — which is what Kant, not Hegel would call it — is that one can only be the very subject of the “I”, and that this subject seems not to have any objectivity to it, as I do not sense or intuit it as an object. If we think of objectivity as only existent in feeling, we fail to see how thought has its object, and that hence, there is objectivity of thought. For Hegel, the subject, the “I”, has objectivity, conceptual objectivity, it has the capacity to be an object of thought, as well as at the very same time being the subject, or the “I” that thinks — it is a singular-universal, self-thinking thought. It is concept.

“Of course, if the “I” is not grasped conceptually but is taken as a mere representation, in the way we talk about it in everyday consciousness, then it is an abstract self-determination, and not the self-reference that has itself for its subject matter. Then it is only one of the extremes, a one-sided subject without its objectivity; or else just an object without subjectivity, which it would be were it not for the awkwardness just touched upon, namely that the thinking subject will not be left out of the “I” as object. But as a matter of fact this awkwardness is already found in the other determination, that of the “I” as subject; the “I” does think something, whether itself or something else. This inseparability of the two forms in which the “I” opposes itself to itself belongs to the most intimate nature of its concept and of the concept as such; it is precisely what Kant wants to keep away in order to retain what is only a representation that does not internally differentiate itself and consequently, of course, is void of concept.”16

The “I” of representation is the “I” as one-sidedly grasped, either as the active subject that thinks, or the passive object that is thought. The fact is that we can only comprehend the “I” by seeing how the subject is the object, or how both subject “I” that thinks, and object “I” that is thought are one and the same while at the same time being absolutely different. Once we grasp the unity (singular-universal “I”) of unity (singular “I”) and difference (universal “I”), we succeed in comprehending the most intimate nature of the concept. The feeling of awkwardness is the result of one clinging to an ossified representation, which is thought of as not succumbing to this most intimate nature. The consequences are not only metaphysical, but also perceivable in spiritual expression:

“If the Kantian philosophy subjected the categories of reflection to critical investigation, all the more should it have investigated the abstraction of the empty “I” that he retained, the supposed idea of the thing-in-itself. The experience of the awkwardness complained of is itself the empirical fact in which the untruth of that abstraction finds expression.”17

Would Kant have said that the thing-in-itself is the abstraction of an empty “I”? I do not believe so. As I’ve mentioned above, the thing-in-itself is uncontained by the “I” for Kant, not within the reach of the concept, not graspable as a moment of the concept’s movement. And as we’ve said above, every object of thought in the concept, is not merely anything out there, but always occurs within the circular positing of the “I” to itself. A relationship to an object of thought is a relationship one has to oneself, since one has made themselves one with thinking objectivity. Kant’s thing-in-itself is in itself, for him, i.e. an abstraction of the empty “I”.

How can awkwardness be an expression of untruth, resulting from the above-mentioned empty abstraction, the static representation of the “I”? Hegel is making a point about aesthetic, or more precisely, humoristic disposition as an expression of metaphysical thinking. As I’ve quoted him above, Hegel finds the awkwardness laughable. To him, the “I” is a funny circle with a quirk. No need to shy away and rigidly assert ourselves against it in the face of the quirk, no need to refuse to come to terms with it. We’re always-already quirky circles, and better to take responsibility for it by asserting ourselves through and as these quirks, as it is solely Spirit that has this power in a self-conscious manner. Confronting, acknowledging, apprehending, comprehending and laughing with the quirkiness is a reconciliation with truth and a sign of metaphysical insight into the nature of the “I” that knows it to stay self-same through its falling apart, as it simply rejoins itself again. We can't help but to have these quirks. And the more vicious the circle is, the funnier it is.18

“The triumph of the Kantian critique over this metaphysics consists, on the contrary, in side-lining any investigation that would have truth for its aim and this aim itself; it simply does not pose the one question which is of interest, namely whether a determinate subject, in this case of the abstract “I” of representation, has truth in and for itself. But to stay at appearances and at the mere representations of ordinary consciousness is to give up on the concept and on philosophy. Anything beyond that is branded by the Kantian critique as high-flown, something to which reason has no claim. As a matter of fact, the concept does fly high, rising above what has no concept, and the immediate justification for going beyond it is, for one thing, the concept itself, and, for another, on the negative side, the untruth of appearance and of representation, and also of such abstractions as the thing-in-itself and the said “I” which is not supposed to be an object to itself.”19

The thinking “I” flies. It is its own justification of itself for the reason of being itself, beyond untruth of whatever has no concept, of what is vacuous and unthought. The “I” is not only a funny circle, but also a flying circle. Free spirits laugh and fly above heaviness that clings to fixed and vacuous representations that inhibit the overflowing hilarity of our vicious circularity. They overcome awkwardness in a perspectival shift through the catharsis of humor. That is, on the spiritual side. On the side of metaphysics, this circularity is rigorously worked through, inclusive of all the difficulty that this education of Spirit entails.

For Kant it is sensuous reality that is objective, whereas the concept is seen as deficient or untruthful. It is not a coincidence that Zarathustra in Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra says,

“The ostrich runs faster than the fastest horse, but it also sticks its head heavily into the heavy earth; so too the human being who cannot yet fly.”20

There’s two — complementary — ways to interpret sticking one’s head in the heavy earth. Firstly, Kant stops short at the quirkiness of the circle and reverts to an attempt to ground the “I” in an empty representation qua thing-in-itself, sticking his head in the sand as the refusal to apprehend the concept in its becoming. Secondly, by rejecting the flight of the concept above representation and mere appearance, he reduces objectivity to sensory reality, or feeling and intuition, thereby holding on to finite and transitory earthliness, or nullity.

To summarize:

Awkwardness is felt because of the self-othering movement of the “I”.

Kant has an inability to self-justify the concept’s flight above finitude.

Kant gives up on the concept by instantiating an a priori delimitation (thing-in-itself as empty representation of the “I”) as the justification for sticking his head in the semblance of edification, attempting to ground himself in sensuous reality.21

The Metaphysics and Spirituality of the comical “I”

Is Hegel laughing at Kant for his awkwardness? I’d contest this, and claim that Hegel finds Kant’s claim of the “I” being awkward comical, which is not the same. The quirky torsion, or paradoxical circle which is the “I” is essential to its existence. If Hegel thought Kant was to be laughed at, he would just point to a contradiction that Kant wasn’t aware of. But Kant was, and this led him to his complaint of awkwardness. The difference lies in how the contradiction is dealt with, metaphysically and spiritually.

In his Lectures on Fine Art, Hegel writes: “In such a case” of, for example, lampooning another, “[one’s] laughter is only an expression of a self-complacent wit, a sign that [one is] clever enough to recognize such a contrast and [is] aware of the fact.”22 Kant was aware of the contrast, or the self-opposition of the “I”, to a certain extend at least.23 The feeling of awkwardness is the expression, the spiritual result of his metaphysics that could not account for the ontological absoluteness of contradiction. The speculative metaphysics that does account for this, reconciles with the unity of the “I” as a self-contradiction. It does not overlook, or look away from it but faces it and apprehends it movement, inclusive of its negative moments. This type of speculative metaphysics that reconciles with contradiction has the same function as the art of comedy. There is an analogous reconciliation to be found in comedy, or comicality, in the form of the catharsis of laughter. Hegel’s theory of comedy posits that

“the comical as such implies an infinite light-heartedness and confidence felt by someone raised altogether above his own inner contradiction and not bitter or miserable in it at all: this is the bliss and ease of a man who, being sure of himself, can bear the frustration of his aims and achievements. A narrow and pedantic mind is least of all capable of this when for others his behaviour is laughable in the extreme.”24

To be raised (and fly) above one’s inner contradiction does not imply the “I” to be the mere abstract fixed point above its representations, but, to the contrary is a reconciliation with the whole of its self-othering movement. And it is thus that we are to understand being raised above contradiction, not as being raised to a neutral, or objective meta-perspective that is detached from contradiction, but is one with it and yet undisturbed by it. Hegel is not mocking contradiction, nor is he mocking Kant for being contradictory. He sees the “I” as being logically contradictory in a metaphysical sense and hence comical in its spiritual actuality.

The feeling of awkwardness is a spiritual effect with a metaphysical cause, mediated by an implicit metaphysics. By this mediation the “I” is revealed directly as inwardly self-dissolving, and it is up to us how to behave with it, light-heartedly, comically, and taking flight with the concept, or rigidly, pedantically and awkwardly shying away from its naked truth. The choice might seem clear, or too self-evident to be true, one-sided perhaps. But just as much as the Phenomenology of Spirit is the funniest book in existence according to Lacan, it does — like Hegel says in its Preface — not only repeatedly plunge us into doubt, but its journey consists of the state of doubt itself, the pathway of despair, and so is fundamentally tragic as well. Absolute Knowing, or the rejoined unity that Spirit finds through its recollection of its shapes and them being torn apart, does not consist of a new-found edification, a point at which one can finally stop having to work with the shattering of oneself, it simply inaugurates the process for Spirit to deal with negativity on a higher order, namely, proper philosophizing.

In his Lectures on Fine Aesthetics, Hegel brings out his theory of art, including comedy. What interests us here is not the truth of Hegel’s theory about ancient comedic plays, but the way in which Hegel thinks about Spirit as comical, especially in relation to the “I”:

“What is comical […] is the subjectivity that makes its own actions contradictory and so brings them to nothing."25

And yet again, just like the “I” perseveres in its dissolution, comical subjectivity does not end up in an annihilation by bringing actions to nothing, to the contrary,

“[the] subjective personality alone shows itself self-confident and self-assured at the same time in this dissolution.”26

The subjective personality, or the “I” bears the dissolving and can express the weirdness in a manner that is not unreconciled and awkward, but in a catharsis of laughter. Because “Comedy”, as Hegel says “has for its basis and starting point […] an absolutely reconciled and cheerful heart.”27

The “I”, as a true infinite, as a beyond of finitude that includes it all the same is visible “[i]n comedy, [for] it is subjectivity, or personality, which in its infinite assurance retains its upper hand[.]”28 The negative unity of the “I”, which is only concrete and truly infinite by abiding, can also be expressed as victorious in the art of comedy according to Hegel:

“In comedy, there comes before our contemplation, in the laughter in which the characters dissolve everything, even themselves, the victory of their own subjective personality which nevertheless persists self-assured.”29

Comedy expresses the intrinsically comical nature of the “I”, as unfazed, victorious, confident, free and infinite — a funny and quirky circle.

“[comedy shows us] the inherently firm personality which is raised in its freedom above the downfall of the whole finite sphere and is happy and assured in itself. The comic subjective personality has become the overlord of whatever appears in the real world. From that world the adequate objective presence of fundamental principle has disappeared. When what has no substance in itself has destroyed its show of existence by its own agency, the individual makes himself master of this dissolution too and remains undisturbed in himself and at ease.”30

The power of comedy, or the comicality of Spirit’s actuality gives us a profound insight into the metaphysical structure and movement of the “I”. Speculative philosophy with its dialectical logic gives us an insight into the funny circularity of the “I”. Metaphysical thinking, and aesthetic, or performative expression are thoroughly interlinked. The incapacity to hold fast to oneself in the loss of the representation of the self, the negative moment of the concept’s becoming, has far-reaching consequences for how one comports oneself in the world. To re-iterate once more, I will give the final word to Hegel:

"[…] the individual self is not the emptiness of this disappearance but, on the contrary, preserves itself in this very nothingness, abides with itself and is the sole actuality. [...] What this self-consciousness beholds is that whatever assumes the form of essentiality over against it, is instead dissolved in it — in its thinking, its existence, and its action — and is at its mercy. It is the return of everything universal into the certainty of itself which, in consequence, is this complete loss of fear and of essential being on the part of all that is alien. This self-certainty is a state of spiritual well-being and of repose therein, such as is not to be found anywhere else outside of […] comedy."31

Hegel, G.W.F. Science of Logic. Cambridge University Press. p. 514.

In other words, I am not simply what I am.

Ibid. p. 514.

Ibid. p. 514.

Ibid. p. 514.

By not being what I am, I am simply what I am.

“It is one of the profoundest and truest insights to be found in the Critique of Reason that the unity which constitutes the essence of the concept is recognized as the original synthetic unity of apperception, the unity of the “I think,” or of self-consciousness.” - Ibid. p. 515.

Ibid. p. 515.

Ibid. p. 515-516.

Ibid. p. 516.

Ibid. p. 516.

Ibid. p. 691.

Ibid. p. 691.

Ibid. p. 691.

Ibid. p. 691-692.

Ibid. p. 692.

Ibid. p. 692.

What's so funny about vicious circles? Take for example those moments in life where a friend makes a joke and you laugh and build on it, and then they laugh and build on it, which makes you laugh and build on it, to the point of this circle going on and on and becoming extremely silly, ending up in a point where you are just laughing at each other's laughing.

Ibid. p. 692-693.

Nietzsche, F. W. Thus Spoke Zarahustra. Cambridge University Press. p. 154.

There’s many more connections that could be made here, which is beyond the scope of this article. For example the following quote by Zarathustra: “Not by wrath does one kill, but by laughing. Up, let us kill the spirit of gravity! I learned to walk, since then I let myself run. I learned to fly, since then I do not wait to be pushed to move from the spot. Now I am light, now I fly, now I see myself beneath me, now a god dances through me.” Ibid. p. 29.

Hegel, G. W. F. Aesthetics: lectures on fine art. Clarendon Press. p. 1200.

The awkwardness he felt is a spiritual expression of the metaphysical way he went about contradiction, in this case of the “I” by putting a stopgap on the thought of its self-opposition by positing a representation that abstracted from it.

Ibid. p. 1200.

Ibid. p. 1220.

Ibid. p. 1236.

Ibid. p. 1200.

Ibid. p. 1199.

Ibid. p. 1199.

Ibid. p. 1202.

Hegel, G. W. F. Phenomenology of Spirit. Oxford University Press. p. 452-453.

Really great article with many “memorable moments” in terms of things that stood out to me as insightful. I will say that the concept of representation was of particular interest to me, and this section really put so succinctly the risk of autonomous representations (to incorporate Daniel’s language);

“It’s not that I make use of the “I”. I am the “I”, the concept, pure self-consciousness. The “I think” that accompanies representations seen as a fixed point halts the thought of it. The idea that the “I” is a means, is subsequent way in which this representation of the “I” can stop us from thinking the “I” for itself, on its own terms, as a unity of its self-contradiction. A metaphysics that relies on a representation of the “I” as a kind of meta-perspective outside of what it contains, that rejects the comprehension of its logical moments as a unity, reveals something spiritual about the very “I” proclaiming it.”

Yes! Indeed. There’s no way for the “I” not be to be further indicted, even in relying on it’s perspectival absence.

I really appreciated how you brought in comedy to this paper. All in all it made me think that we should be more willing to laugh at ourselves.

I want to consider a word play connection between “I” = “I” and eye for an eye vs turn the other cheek in the second testament. It seems that the turning is necessary for us to not block the movement of the eye/I. As you said it’s a stoppage of thinking when the I is detached. Yet turning the cheek (think circle) allows us to see the unity of the contradiction. More to refine here for sure but I wanted to share.

Thank you for the article!

Incredible insight and an incredible piece of writing. You write very well, and I always find pleasure in the eloquence and clarity of your prose. This section was gold:

'Confronting, acknowledging, apprehending, comprehending and laughing with the quirkiness is a reconciliation with truth and a sign of metaphysical insight into the nature of the “I” that knows it to stay self-same through its falling apart, as it simply rejoins itself again. We can't help but to have these quirks. And the more vicious the circle is, the funnier it is.'

Your focus on comedy was also excellent. 'The power of comedy, or the comicality of Spirit’s actuality gives us a profound insight into the metaphysical structure and movement of the 'I'.' - I utterly agree and love how you elaborated on the case.

Well done sir.